|

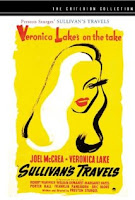

| Photo: Movie Goods |

A director of escapist films goes on the road as a hobo to learn about life... which gives him a rude awakening.

Of all of the films that have inwardly examined Hollywood and the filmmaking process, few have shown the exuberant wit of Preston Sturges' 1941 screwball dramedy Sullivan's Travels. Aside from obvious parallels to the satirical 18th century novel Gulliver's Travels, Sturges' satire provides subtext that's weighty and sends a confusing, if not misunderstood message about comedy, Hollywood, pretentiousness, class disparity, etc. What follows is an attempt to piece together some of Sturges' strongest convictions within a work that's masked with screwball fluff.

Sullivan's Travels begins with the protagonist, John Sullivan, telling his studio boss that he's tired of making shallow, lifeless goofball comedies that lack any substance or cultural value; what he longs to do is explore the plight of the lower class and the impoverished. He wants to hold a mirror up to real life and make a real statement about the sorrows of humanity. Much to the dismay of his studio boss and a few close companions, he makes a boldly ambitious decision to take the road in full hobo disguise and experience the pathos of vagrancy himself.

More after the jump...

|

| Photo: IMDB |

Sullivan's misadventures begin to take on a farcical tone. The studio attempts to turn the whole operation into a sensational publicity stunt, aggrandized with a screwball-inspired land yacht chase scene that satirizes the hierarchy of class. Sullivan hitchhikes and hops trains, but seems to always end up back in Hollywood, where his luxurious, high-class life awaits.

Along the way, he encounters "the girl", as she's credited, or in other words, the archetypal young, beautiful blonde who we know will greatly factor into the story. Sullivan jacks a car (or does he borrow it?) with the girl, and the two ride off, only to be pulled over and jailed. A policeman at the Beverly Hills police station asks Sullivan, "how does the girl fit into the picture?" Sullivan snaps back, "there's always a girl in the picture, don't you go to the movies?" This line, coupled with Sullivan's inability to escape his high-class lifestyle, is a satirical bit about Hollywood's stranglehold and saturation of the filmmaking process.

After several failed attempts, Sullivan and the girl (now both dressed as hobos) finally go full "method" and become absorbed in the world of vagrancy. But after a short period of time living out of homeless shelters and eating in soup kitchens, Sullivan calls it quits and reenters the world of high-class privilege, fully ready to tackle his next ambitious social commentary feature, O Brother Where Art Thou?. However, in an attempt to thank the homeless by going around and lending $5 bills, he's ambushed by a hobo, who not only steals his shoes and money, but also throws him in a train boxcar that's leaving the city. Incidentally, the hobo is then run over and killed by an oncoming train, and the hobo, while unrecognizable, is believed to be Sullivan because of his shoes. Sullivan ends up in another railyard, where he's faced with amnesia as a result of the blows he took to the head. He assaults a harrassing railroad worker, and because he's unable to identify himself to the authorities, he's sentenced to six years of labor camp.

|

| Photo: Film Forum |

The big revelation comes when Sullivan and his fellow prisoners attend a showing of Walt Disney's Playful Pluto cartoon. Sullivan, fully out of character and in the mindset of a downtrodden prisoner, notices the hearty laughter and sheer joy on the faces of his fellow prisoners, and he too begins to indulge. Sullivan originally set out to share the mindset of the impoverished and less fortunate, but his ambitions were disillusioned; these prisoners only want to get away from themselves and their problems, if only for a moment, to have a few cheap laughs. In the end, Sullivan does hold a mirror up to real life, but it's showing something different than what he originally envisioned.

What's ironic about this scene, however, is that the Playful Pluto cartoon expresses a type of physical comedy that predominantly features Pluto being trapped and/or stuck -- much like the predicament all of the prisoners face. Sturges' message here is that the inherent nature of film is to express and depict, in some way, shape or form, real life. This notion confuses the subtext from earlier, when Sullivan was unable to keep Hollywood saturation out of real life struggles. The end result, in this intance, is a message that seems to both delegitimize AND celebrate escapist comedy. The way I like to interpret this, however, is that Sturges is advocating the interrelationship between escapist cinema and thought-provoking comment. Both are elemental to this film and to the framework of Hollywood filmmaking in general.

|

| Photo: Row Three |

Sullivan's Travels can be called many things, from screwball comedy to ambitious social commentary. It satirizes not only Hollywood pretentiousness and overambition, but also escapist comedy; it also celebrates both. Sturges recognizes that Hollywood and real life often share the same wavelength, and he emphasizes that the burdens and sorrows and troubles of humanity can, and likely will, manifest no matter what kind of picture is being made. He also communicates some important messages about class disparity in the early 1940s; poverty, while unappealing, should not be shunned or thought of as utterly devoid of dignity. Wealth, on the other hand, as glamorous of a lifestyle as it is, can seriously hinder one's sense of social purpose. For most of the film's duration, Sullivan's ambitious, yet misguided pretentions cloud the fact that all of the proleteriats of America need is lightweight comedy. To place Sullivan's Travels and all of its latent messages in the context of the Great Depression, the time in which the film was made, would wholly idealize the spirit of the times.

Trivia:

- John Sullivan plans to make a movie entitled O Brother Where Art Thou? -- a title borrowed by Joel and Ethan Coen for their 2000 film of the same title.

- Veronica Lake ("The Girl") made this movie while pregnant.

- In 2007, the American Film Insitute ranked this as the #61 Greatest Movie of All Time. It was the first inclusion of this film on the list.

No comments:

Post a Comment